What manuals don’t say about life with a facial recognition video doorbell

Some consumer electronics makers try to get ahead of surprises by writing in a manual about some possible non-satisfying features that buyers might encounter upon using their purchase.

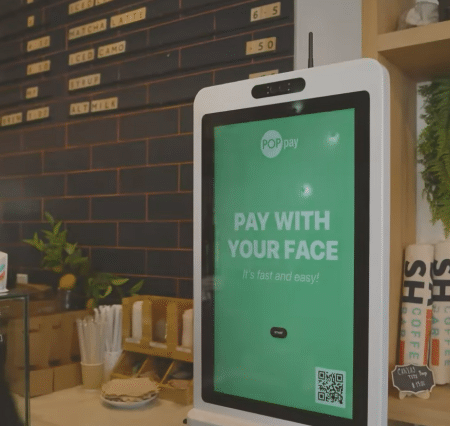

Buyers of autonomous facial recognition doorbells and associated AI-enabled indoor and outdoor cameras know the marketing: omnipresent, unblinking monitoring of one’s home and its occupants.

The manuals may not alert everyone, however, to how they can lose control of their investment, antagonize their neighbors or inappropriately feed a vendor’s database of faces.

This is a timely reminder for people like those in Scotland – just 36 so far – who are being given video doorbells, at least some of which will be Amazon’s Ring system, free of charge by the government.

According to reporting by the Glasgow Times, residents who fit a profile – vulnerable to crime and financial harm or door-to-door scams – are getting the hardware, software and data storage.

What they probably are not getting is news of a man living in the U.S. state of Ohio who cooperated with a police request for a short, discrete span video coverage from some of the 21 Ring cameras in and outside his home.

The police last fall wanted information on one of his neighbors, suspected of being involved with illicit drugs, according to U.S. news publisher Politico.

With the camel’s nose in the tent, the police asked the resident for more before Ring staff notified him that the company had been served a warrant to deliver any footage from all or most of his cameras that the police demanded. Ring executives agreed to do it, and the resident had no say in the matter.

In another surprise for many owners of surveillance doorbells, this one also in the United States, The New York Times informed its New York City readers who own apartments in co-ops need no municipal blessing to put a camera on their unit’s door. If the co-op’s board approves it, up it goes.

That means that as often as not, one unit owner’s lens will record all that happens in front of it; all passersby, all visitors to the neighbor’s apartment and even brief glimpses into that apartment.

A final example of a potentially unhappy newsbreak also comes out of the United States – this time out of the state of Florida.

A pair of information security insiders (one of whom is a hacker) accuse Anker Tech, maker of eufy cameras, of logging people recorded despite the fact that Anker says it does not.

The pair have sued Anker, saying unique identifiers are assigned to every face a camera sees, and the identifiers stored in the cloud, according to United Kingdom-based technology publication The Register.

The case was filed in Florida and has been transferred to the state of Illinois, home of the Biometric Information Privacy Act.

The accusation was made public in November and still is little-known. The Register says a VLC media player is all anyone would need to tap into a eufy camera. Going to the cloud were biometric identifiers and a video thumbnail.

The Register story lists the many camera models cited in the suit as being vulnerable. There has been no statement in response from Anker.