Thailand’s blockchain digital ID infrastructure – an ecosystem in an ID ecosystem

Thailand is progressing rapidly with enrollment into its blockchain-based biometric digital identity infrastructure operated by the National Digital ID Company Limited (NDID), with registration up by 50 percent since November at 9.2 million. Now half the population is eligible to be part of the system as it readies to introduce verifiable credentials and a digital wallet.

Various schemes and projects involving telcos and convenience stores have been launching in the country of 70 million. NDID is not a digitized version of the national identity card or even a digital identity in itself, so Biometric Update spoke to its CEO, Boonsun Prasitsumrit, in Bangkok to learn what it is and the role it plays in the identity ecosystem and financial sector.

The beginnings of a public-private trusted ecosystem

Rather than the Thai government building a national digital ID system, it created a way to link service providers and identity providers (IDPs) to allow the digital sector to flourish and innovate. It also decided not to be as directly involved, establishing a private company to oversee the project.

“NDID in the beginning, four years ago, we decided that IDPs were not only to be banks,” says Boonsun Prasitsumrit in the NDID HQ, “it could be anything, anyone who qualifies to do it: bank, mobile network, fintech.”

At the outset, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society realized they were “sharing the same pain point: the KYC process,” says Prasitsumrit. The ministries helped establish the Digital Identity Committee in 2017.

The country has the Thai National ID Card, which has holder details embedded in a chip. There is near universal coverage for citizens, but the smart card chip is rarely used for opening new accounts or accessing new services, says Prasitsumrit, as the standards on how to use the chip have not been clear. People generally still have to attend government offices and banks in person with their cards and often photocopies of their ID.

The Digital Identity Committee decided to develop the infrastructure to unlock identity for other areas via a trusted ecosystem. Health and education were part of the original discussion, but emphasis was placed on banking then financial and insurance services. NDID was established as a public private partnership that is 36 percent publicly owned.

“If it’s government, it will take some time,” notes Prasitsumrit. As it was for all things digital, it needed to work faster than a government agency can.

The majority of NDID’s sixty-plus shareholders are in the financial sector, such as the Thai Banking Association, along with the stock exchange and Post Office. The Bank of Thailand developed a regulatory sandbox for the system and now eleven banks are part of it.

In 2018, the Electronic Transaction Development Agency (ETDA) likewise worked on national standards for levels of assurance aligned with those of NIST. Legislative changes in 2019 allowed the first use of the system by the end of that year.

More than nine million are now enrolled and 35 million (up from 30 million in November 2022) are now at the country’s highest assurance level, 2.3, which requires a smartcard ID, check against the government’s D.Dopa national IDP and face biometrics.

With these, Thai people are ready to enroll in NDID the next time an opportunity presents itself online, such as wanting to open a new bank or securities account or taking out a loan.

Both a blockchain and bypass

NDID is a “connecting platform,” says Prasitsumrit. As a decentralized ledger, NDID cannot see any of the information passing across it between banks, users, IDPs and authoritative sources, but simply a log of timestamped access requests.

Users visit a bank in person in the first instance. People are not going to banks to get NDID, says Prasitsumrit, they are going to conduct transactions. They hand over their smartcard ID and undergo a biometric check, where bank staff or cameras compare the person with the photo held in the card – the trusted source. Banks can check fingerprints, but this is not popular. If there is no photo in the system, the bank can take a photo to enroll a person into NDID.

“Thai people don’t know that their data at the bank is at the highest level,” says Prasitsumrit, “they are ready to use [NDID].”

When going through NDID enrollment they would not be aware of the company as a brand unless they read the full terms and conditions, says Prasitsumrit, explaining how the platform is very much in the background.

The millions of users enrolled “know there is a difference” even if they never have any interactions with NDID.

This is because they can now open any account or product with registered providers by selecting online the bank where they underwent the KYC and so do not need to visit in person or prove ID again.

Dropout rates for new service sign-ups are falling.

When prompted during sign up, a user selects the bank where they are already enrolled as their ID provider. The target bank – the relying party – sends a request to the selected bank via the NDID ledger.

The bank acting as IDP then notifies the user that it has been selected for ID proofing and takes the user through verification in its own app on their phone, using face biometrics, PIN and registered mobile number.

When the IDP bank has confirmed ID, it notifies the relying party bank back through NDID, with this logged in the blockchain. It then sends the user data to the new bank directly, outside the NDID platform. The user completes registration by creating a new password.

ID is “nothing to do with NDID until there’s a request from a relying party through NDID for an identity provider,” explains Prasitsumrit, as the blockchain neither sees nor stores sensitive data.

A relying party can verify across multiple IDPs as wells as multiple authoritative sources in the process, such as credit scoring agencies.

People have to redo KYC every two to three years, or if they get a new ID card.

Fees are a cost saving

NDID’s business model is taking a fee for connecting relying parties and IDPs.

“It’s like the credit card model, a hundred percent [of the bill] goes to the relying parties” says Prasitsumrit. It is a fixed fee, not a percentage and includes two prices: a fee to the IDP which accounts for 98-99 percent of the price, with the remaining fraction going to the NDID.

As part of the structure of establishing the NDID, the company does not and cannot control the fees. The process is still a cost-saving for banks compared to having to take a new customer through KYC.

The NDID fee is discounted by eight percent to government departments using the system.

Verifiable credentials and a digital wallet

NDID is also launching a wallet for verifiable credentials. “For eKYC, we really need a high level of assurance. The bank itself can confirm to open the wallet by using biometrics, so we can ensure the owner of the wallet is really him or her,” says Prasitsumrit.

The company is working with a government department on a proof of concept for VCs for paperwork which a user can then share with their bank.

Universities are already in talks about providing certificates and transcripts as VCs to the wallets.

NDID and MNID: AIS, True and DTAC

Thailand has three telcos – AIS, DTAC and True – which are becoming IDPs. Their scheme is Mobile Network ID (MNID). The process has been underway for a couple of years but is proving slow as the telecom regulator, the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission, is the operator.

The MNID system serves its mobile customers rather than being a competitor to NDID and the two systems will merge under the ETDA. Its chairperson wants NDID, MNID and government services (D.Dopa) to be interoperable.

Technical discussions are underway to determine how a relying party in the NDID platform can request ID proofing through AIS or DTAC and vice versa. Relying parties can choose to go via NDID or potentially MNID, but the hope is that a unified systems will offer cost savings.

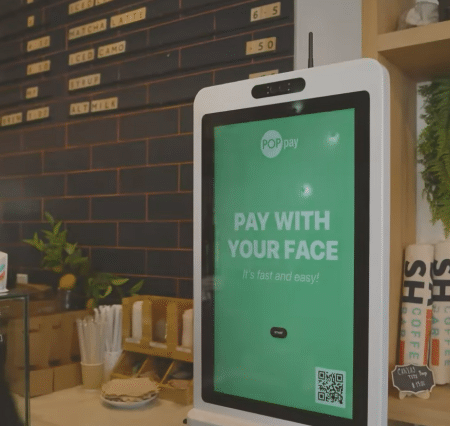

AIS has two ID capabilities on the go. Along with DTAC, it can partly use NDID, do its own checks or use partner banks. The operator has around 20,000 service points across the country. A relying party in NDID can request a person to visit an AIS location to have their ID card read. In this instance, AIS a service provider to NDID – not an IDP. It undertakes biometric comparisons at its kiosks. The person does not need to be an AIS customer.

AIS is also working on its own digital ID for which users would have to be AIS subscribers.

The hope is that when the systems are fully integrated, Thais will effectively have mobile digital ID (rather than just eKYC).

Growing digital ID landscape

Alongside NDID as the main infrastructure, and MNID which will join it, there is a scheme for digitizing the national ID within the Thailand Digital ID Framework (2022-24). Citizens can take their cards to local government agencies for chip reading and biometric checks to generate the ID in an app.

The Digital Government Development Agency (DGA) is also working with 7-Eleven whose stores are near ubiquitous. Staff authenticate the user against their card details and chip content and send the data back to the DGA which cross-checks with D.Dopa to create a digital ID.

A pilot system is allowing Thais to use mobile digital ID on domestic flights.

“The government doesn’t have an application or system similar to the banks’, they can’t provide non-face-to-face [ID],” says the CEO. The national ID card issuer is developing mobile applications, similar to mobile banking, but with fewer than 50,000 users and few transactions.

Government services are beginning to accept digital transactions such as for paying land tax. In the future, government departments will not be able to refuse the use of digital ID, nor will private providers.

The country is aiming for ten million mobile digitalized ID holders by the end of the year.

The role of biometrics in banking is increasing. The Bank of Thailand is introducing new requirements for face biometrics authentication for certain transfer thresholds.

The future: interoperability and regulation

The NDID system is still operating within a regulatory sandbox.

“In the future, our concern is about laws and regulations because we have an app already, but we don’t have regulations,” says Prasitsumrit, “so now the ETDA is going to issue many regulations and we also need to apply for the license, not just NDID: the banks need to apply for the license.”

NDID is also hoping to test its services with other countries and has an agreement with Mastercard on international issues. The CEO hopes that Thai people will be able to use their mobile banking as proof of identity abroad in the future.

Whatever happens, he hopes to maintain high standards: “Digital ID proving is very important. Once you relax or you loosen that standard, then any fraud transaction that should happen – there’s no point having NDID.”