Online proctoring biometrics use fails to meet Canadian legal threshold, report says

Online proctoring tools for conducting remote exams do not go far enough to ensure free, clear and individual consent from Canadian students whose biometric data they collect, according to a new report published by the University of Ottawa and supported by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

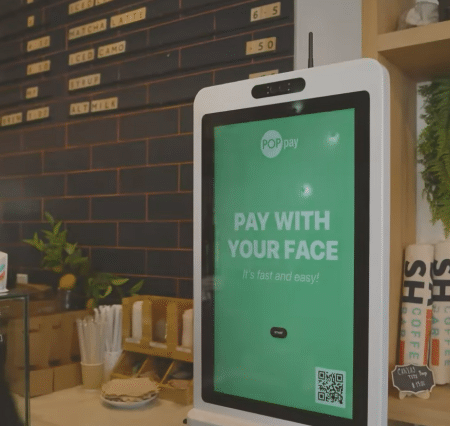

With in-person learning disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, many institutions turned to software platforms as a way to conduct examinations. Often based on artificial intelligence, tools such as Respondus, Monitor, ProctorU, Examity and others use data mining and facial recognition to monitor for cheating—and present what Céline Castets-Renard, the Law Professor who led the project, called “legal issues of socio-economic discrimination and privacy.”

The report points to familiar issues with AI discrimination, specifically “the overreach of power such as public surveillance or police surveillance using AI facial recognition software, with a potential for discrimination, such as race, gender and age biases.” But it also identifies the risk of certain socio-economic and situational factors that could trigger unwarranted software alerts. According to the report, “a domestic pet who makes noise, such as a bark or a chirp, during an online proctoring exam has been identified as a cause for flagging a potential cheating incident.” Pets, children and other audio-visual variables can make the proctoring software think something suspicious is going on when it is not—a problem compounded in large, multigenerational homes.

Biometric tools, such as facial recognition, are susceptible to similar errors. “Biometric keystroke analysis which serves to track keystroke data, eye tracking which monitors and analyses eye movements, audio monitoring which records and monitors students sonically, and facial detection are all methods that are used by some proctoring software,” says the research report. And all come with unacceptable risks that the technology will mistakenly flag certain variations in data as cheating.

The report concludes with a series of recommendations pertaining to how AI is defined and categorized, and how human oversight of evolving surveillance technologies can help maintain transparency and reduce error and bias. The final recommendation tidily summarizes the researchers’ findings, calling for “a collective reflection on whether to prohibit certain uses of AI, and the means to determine how to identify such prohibited uses.”