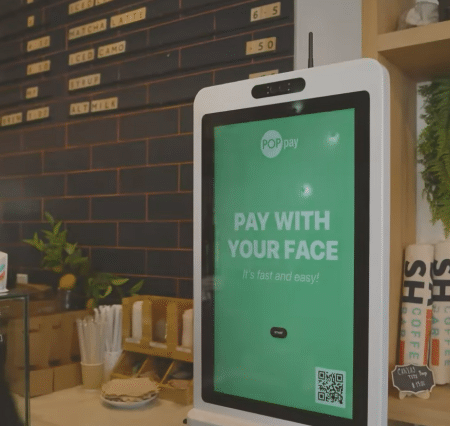

Datasets driving facial recognition development fueled by data privacy violations

The shift from manual feature engineering to neural networks that supercharged facial recognition also created a market for face data without regulation or oversight, leading to a host of problems, according to a researcher and activist.

‘Researchers Gone Wild: How our face powered the rise of biometric surveillance technologies’ was presented by Berlin-based researcher and CV Dazzle Founder Adam Harvey. Harvey is also co-founder of Exposing.ai, an online tool which can tell people if their images have been used in training facial recognition models.

The presentation was hosted and sponsored by the Center for Ethics, Society and Computing (ESC) at the University of Michigan.

Harvey’s interest in facial recognition and surveillance was born out of his experiences as a photographer in New York City, just as cameras were beginning to proliferate as never before in cellular phones. This was coincident with the post-9/11 rise of interest in and funding for research into biometrics for security applications, he notes.

Facial recognition was mostly confined to controlled-capture scenarios, and the algorithms not yet sophisticated enough for broad application.

“A surplus of data being posted online containing biometric information and a growing need for new biometric technologies” converged as a source for datasets, Harvey says.

The advent of face biometric algorithms based on convolutional neural networks created unprecedented demand for facial data, and the internet, Harvey explains, provided the supply chain.

Labeled Faces in the Wild was a precedent-setting dataset, he argues, not just because it provided the data that would allow neural networks to automate the feature-engineering portion of the task of training the algorithm. It also set a precedent ethically, according to Harvey.

Various datasets were subsequently developed, many of them with “in the Wild” as part of their title.

One research paper’s dataset would lead to other datasets, he says, some of which are not easily available.

The Duke MTMC Dataset moved the data-collection process offline, and “eventually became the most popular, widely-used, in the world, dataset for multi-target multi-camera” with numerous citations.

Many other datasets followed the same model of capturing CCTV images for research purposes.

“Isn’t it called ‘CCTV’? Closed-circuit television? And now it’s on the internet,” says Harvey.

Consent was rarely sought for these databases, Harvey says, and even when it was, researchers still included images from people who had not granted it.

He reviews the continued development of datasets, such as MegaFace, which scaled the internet-scraping approach to reach 672,000 faces.

By 2017, Google and Facebook had datasets of roughly 8 and 10 million faces, respectively.

Harvey shared a slide visualizing the proliferation of the Duke MTMC dataset to other researchers around the world for industry, academic and military usage.

Backlash builds

When Duke quietly pulled the dataset offline, Harvey says, it was a tacit admission of guilt.

CVPR 2019, which was intended to be based on the use of the Duke MTMC dataset, was cancelled “because the dataset was now in legal limbo.” MTMC was replaced with ReID, which was collected in China, to allow the conference to be held.

Datasets based on Creative Commons licenses have some legal protection, even in cases where they are used for commercial purposes, which actually violates CC restrictions, Harvey says. They are also generally not attributed, which is required by the license they are used under.

The most common source of photos within these datasets is weddings, Harvey has found.

Some of those may have occurred in Illinois, in which case a dataset like MegaFace likely violates BIPA, Harvey warns. The presence of children from California could raise COPPA liability.

Harvey identifies a trend. “It’s just using the same old dirty playbook of taking other people’s data and then repurposing it for something different, and kind of exploiting that for other purposes,” he says. “And you end up with really biased or incompetent face recognition that’s dangerous, inaccurate and should be, frankly, illegal.”

Datasets that drive less bias and higher accuracy still create a “power asymmetry” which is unacceptable, according to Harvey.

In his latest project, Harvey is using synthetic data and 3D-printed objects to create a training dataset to detect cluster munitions, images of which are not available on the internet at scale.

Attendees asked about equivalents to other data-hungry areas of research, how to make the general public understand the level of concern they should have about facial recognition and data sharing, and whether it even makes sense to share anything online.

On the latter point, Harvey says that the community needs to help lawyers develop better licenses, “and we probably need a few class action lawsuits to happen.”