Address trust gap to improve outlook for Nigeria’s digital ID scheme, Academic argues

Taking Nigeria as an example, Babatunde Okunye considers how the lack of trust in African governments could limit the rollout and scope of digital ID schemes, in a commentary published in Data & Policy, Cambridge University Press.

Okunye finds the EndSARS protests of October 2020, where youths took to the street to decry the brutality of the police’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad and were shot at in return, as a pivotal moment in how young people perceive the government.

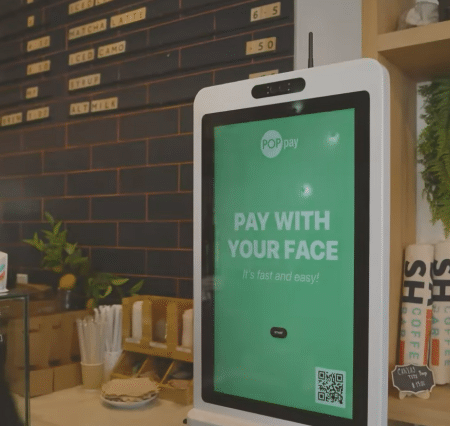

So when the federal government subsequently began on its path to enforce National Identity Number (NIN) registration against SIM cards, suspicion and resistance rose. The move was seen as a function of government surveillance.

Okunye, the University of Johannesburg and Harvard scholar, argues that this shift in perception, and correspondingly low NIN registration levels among the young, threatens the whole NIMC (National Identity Management Commission) project.

“Nigeria’s youth represent the largest segment of the population and significant resistance within this demographic does not bode well for plans to ensure inclusivity and adoption of the country’s ID project,” writes Okunye in ‘Mistrust of government within authoritarian states hindering user acceptance and adoption of digital IDs in Africa: The Nigerian context.’

“In retrospect, given that the relationship that end-users have with the government has a strong influence on their behavior and attitudes towards identity, and institutional mistrust is strongly linked with institutions such as government underperforming, it is probable that if Nigeria’s youth unemployment rate were not so high (42.5 percent) and youths were otherwise profitably employed and engaged within the economy, the resistance demonstrated towards the national ID might have been much less, and the EndSars protests might not have been as severe.”

The scholar sees the NIMC project as one of national development through the delivery of services, reducing waste and tackling insecurity, yet this is no longer how it is being interpreted.

There is hope for Nigeria and other countries. A data protection law would bring clarity and potentially protection for individuals. Okunye also recommends a federated approach with multiple databases and ways to prove one’s identity, rather than the single approach of the NIN, and the NIMC’s linking of databases from a more fragmented past.

“However, perhaps the best response to a fragmented identification landscape where at least 16 IDs held sway in the country is probably not a unified identity landscape where only one ID is used,” writes the academic.

“The former is a failure of coordination and planning within different segments of government who were not under coercion to use this fragmented system, while the latter is perhaps a hurried reaction to the former. This replaces one problem—disorderliness and waste, with a different type of problem—centralized control and an absence of choice and agency for people in the use of IDs.”

He cites the UK as an alternative which functions without a centralized identity database other than the civil registry.

Okunye concludes that many Africans without ID live in places where rule of law and the judiciary are weak means that introducing data protection laws may not protect such people whose data is collected for new digital ID schemes.

“Concrete, technical implementations that make it more difficult to abuse data are critically important. While the provision of legal identity for all by 2030 is an important United Nations sustainable development goal (goal 16.9), human rights considerations are probably more weighty and foundational values that undergird human existence, and should not be watered down or threatened by the pursuit of developmental objectives.”

Looking more specifically at Nigeria, Okunye recommends opening up the registration system to those without feeder documents and “a commitment to using the NIN as part of a federated ID ecosystem without extensive inter-linking and centralization of citizen data.”