Leak of police biometric data won’t change America’s regulation debate

A significant theft of public safety-related biometric data in the United States this weekend will not slow the adoption of facial recognition by law enforcement.

That is despite repeated and rote assurances that any biometric data collected by police is by definition safe from theft or misuse.

There are a number of reports about the servers of police IT contractor Odin Intelligence being hacked over the weekend. It is possible that a facial recognition algorithm called AFR Engine was being used by the police whose information was hacked.

According to technology news publisher Vice, 15GB of data, including biometrics involving unhoused people and criminals, have been stolen and shared. A group Vice described as a transparency organization – Distributed Denial of Secrets – reportedly was given the files and shared them with another Vice Media Group publication.

The data included mugshots and fingerprint biometrics, according to TechCrunch. At least some of the data is reportedly unencrypted.

A leak of biometric data from police was not unexpected.

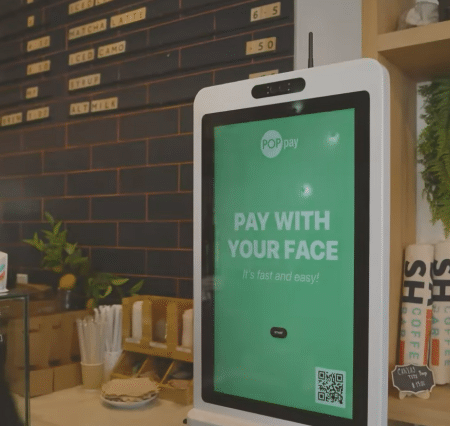

There was a short period, coincidentally around the advent of the pandemic, when governments around the nation were creating moratoriums on governmental biometric identification and surveillance.

Indeed, many U.S. opponents of biometric surveillance blankets said there was no reason to think any law enforcement agency can protect personal data. They are trained no better than any other governmental unit, and their record in one area of their expertise, keeping dangerous people in custody, has blemishes.

But that skepticism has all but disappeared, overwhelmed by a new narrative. Personal and property safety are threatened. Often, people are being told migrants are the threat.

People – especially property owners — are being told America is more dangerous and that cameras are an inexpensive way to stop people from committing crime. Of course, robberies still occur often in banks, gas stations and convenience stores, all of which were among the earliest adopters of in-store surveillance.

Odin’s leak reportedly held thousands of images, including people forced to live in the streets and sex offenders. Other data was collected for tactical plans for raids on criminal locations, according to technology news publication TechCrunch.

Instead of demanding responsibility in how law enforcement holds biometric identifiers, the people most fearful of crime and most able to apply pressure on governments to secure data have bet that they will be left untouched by leaks.

That is a fallacy that will come back to haunt.